You can read all 33 chapters of SPACE CATS

here

Catnip plants thrived along the back wall outside the kitchen windows. In fact, they were practically taking over down by the barn, even pushing up through the gravel in the driveway. As Susan explained it, six years ago she’d been driving east on route 61 and happened to pass a handmade sign announcing catnip plants for sale.

A lovely white-haired lady named Alice was weeding a little garden in front of a modest furniture store. She said that her house in Centralia had fallen into the coal mine that caught fire in 1962 and swallowed the town. Up the road, she still had the tiny store, which offered enough items for sale to outfit a one-room cottage, providing you didn’t plan to sleep in it or sit anywhere.

But there was plenty of catnip, which was why Alice was hoping to make a little walking-around money from it although, as she said, the burbs of Shamokin were mainly dog country and the market was soft.

Now that it was mid-July, the tops of the plants around the farm were already lacy with delicate purple flowers. A keen minty scent drifted through the screen of the patio door, around the kitchen, and into the eager noses of a group of restless cats inside who were hoping I’d open the door for them so they could run out and play.

Along with the fragrance of catnip, the kitchen cats were entertained by a repertoire of songs just outside the east window near the sun room, where a Carolina wren was joyfully singing through his best local bird imitations, to the mortification of a flicker, several catbirds, a cardinal, plus a Baltimore oriole who flew away in disgust.

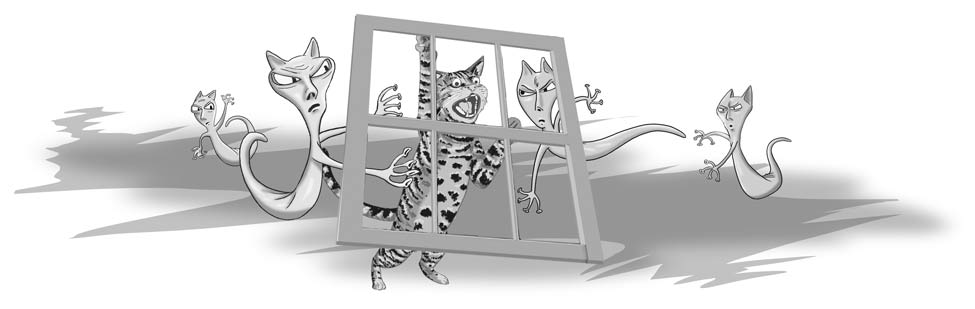

However, as the cats listened eagerly to the world outside alive with their favorite music, this particular morning it seemed as if they may as well go back to bed and wait for Bill to come in from the barn if they were ever to go out and play. Because even though their only barrier to the outdoor life was just a sliding screen door that wasn’t even locked, I wasn’t about to open it for them with Java standing in front of the door and him looking so mad.

Java’s pretty sister Grace was a grey tabby accented with soft white fur that came around her neck to a wide V up her face. She stopped short when she saw the glum kitchen group crowding around the door. “Why isn’t everybody outside on such a nice day?” But then she saw her brother.

“What on Earth have you got around your neck, Java, dear?”

Susan had finally stopped Java from fussing with his bandage by applying what the vet referred to as an Elizabethan collar, or what the cats called the dreaded lampshade. Java stood by the door looking lower than a leaky leech.

Through waves of barely suppressed giggles, Grace finally managing to say, “Move aside and let Ridley open the door, Java — unless you’ve somehow figured out how to do that yourself.”

Susan had put the Elizabethan collar on Java.

She must have recovered from the shock of seeing me open the kitchen door the night before.

“First get this off me.” Java’s voice sounded hollow from inside the plastic cone.

I’d already started edging toward the basement door to go outside by my own private way, but MeMe whispered, “Maybe if you help him, he’ll be nice to you.”

The old saying, ‘no good dead goes unpunished,’ floated through my mind like an epitaph on my tombstone.

Java held himself rigid, head pulled back turtle-style as I popped off the cone with my teeth. When the hated thing clattered to the floor, Java jumped straight up in the air like somebody had dropped a cucumber behind him. The glass door was already open to let in air, so all I had to do was stretch my body up against the screen and slide it open. Java immediately raced outside without a word, which indicated that things would be going downhill for me the rest of the morning, maybe far into the night, we’d have to see how it went.

“Aren’t you even going to thank her?” Grace yelled after her brother, but by then Java was out in the yard with his pals.

After the last cat was outside, I slid the screen door closed. Grace stared at me with renewed horror, since in her lifetime no cat had ever closed a door behind herself, much less turned a knob to open one. Right then, I knew I was in for trouble, maybe get burned at the stake for heresy.

Aww, to hell with cats.

Free for another day, the little darlings ran over to the pine trees at the edge of the yard for their daily duties. Scrape, scrape, scrape. Pine needles flying, clawing bark off the trees. Grace called over to her brother, “You owe Ridley for getting that thing off your neck.”

Java was very busy trying trying to chew an annoying spot of pine resin from his back foot. Nothing stuck like pine sap and he hated the stuff. He called back to his sister, “Ridley’s a big liar! She told me some crazy story last night about going off in flying saucers with blue lizards that look like cats.”

Then he turned to me with fiery eyes. “You made it all up, didn’t you? Even about the metal mice. I had nightmares all night.”

Even if they chased me away with pitchforks and blazing torches, it would have been worth it. Only, just then MeMe came to my defense, calling out, “She’s not a liar! They really were blue and they did fly away with us. Not only that, but we almost never came back!”

Watson and his two brothers, Big Eddy and JJ, swiveled their ears. The three of them were good looking flame points—you know, white Siamese cats with those tan tips and light stripes. Although Watson and Eddy weren’t totally dim, they’d have a lot of trouble juicing up a six-watt bulb. Their other brother JJ was a sweet cat but he’d never have the enough string to twine a bale, if you know what I mean.

Tossing his head at me, Watson said, “Ridley thinks she’s from outer space!”

I crouched in the grass flicking my tail. This wasn’t something I needed anyone to hear just then, or at any other time.

“Wooo wooo. The cat from space,” Java teased loudly. “So beam yourself back to the moon and we’ll be rid of you.”

Grace swatted her brother and he flinched back. “You’re so annoying, Java. Leave her alone.”

MeMe tried to help. “Yeah, Java. Leave her alone because she’s not a liar!”

“That cat lies like a lazy lizard,” snapped Java.

“They’re not lazy,” MeMe insisted. “How many lizards do you know well? I’ve met quite a few . . . they only slow down when it’s cold.”

The ones last night didn’t, I thought.

“So where’d she get such a stupid name?”

“She was a stray.” Watson informed Java. “Bill found her over in Ridley Park west of Philly.”

And I’m like, I wasn’t a stray! I was lost. There’s a difference.

Grace stuck her tongue out at her brother and told the others in a shrill soprano, “Talk about names! Java was named after a cup of COFFEE !”

The girls fell on the grass in hysterics.

The white cats had a fourth brother who Susan originally called Albert Hiss, since that and biting people was what he was best at. Like most of the cats, nobody wanted to adopt him when he was a foster kitty so he grew up on the farm. The Matthews kept all the strange ones so they’d have a good home, which I guess was why they let me stay.

In a desperate attempt to sweeten his wild-eyed Siamese nature, Susan changed Albert’s name to Chocolate, which only worked for her. Edgier than a fly leading a choir of bullfrogs, Chocolate always went around carrying his tail up stiff like a stick of dynamite. He was about as safe as a shark in a duck pond and seemed to have a lot of trouble keeping his nerves on edge. Susan fed him treats and whispered sweet things in his ear, so she was the only person who could pick him up without risking serious personal injury, but everyone else handled him like nitroglycerine. Maybe you know someone like that.

Chocolate was devoted to MeMe, so anyone who disagreed with her had to deal with him. “She’s right, of course,” he informed the others. “Unlike most cats, lizards are cold-blooded.”

With an arch look, MeMe told them, “Everything Ridley said was the truth because I was there!”

Java looked back and forth between his friend MeMe whom he adored, and me, the cat he hadn’t been able to chase away after several good attempts.

“This isn’t the same thing,” he insisted. “I’d believe MeMe no matter what she said, even if it wasn’t true. But I’d never believe anything that cat had to say, even if it were true.”

“Was true,” Watson corrected.

“Were true,” insisted Java, contradicting himself with the subjunctive mood.

When it came to shading the truth, Java preferred to apply motivated reasoning—something his sister called cat logic. Grace was puzzled. “You wouldn’t believe her. But you’d believe MeMe even if what she told you was the same thing. How does that figure?”

MeMe was fed up with all this silly talk. “Ridley was telling the truth. There is a flying whatchamacallit, and it’s parked over the ridge. Some space-lizards that look like cats are trying to fix it right now!” . . . adding in a low whisper, “They’re cold-blooded ‘n mean, and they’re all BLUE!”

Chocolate stood over MeMe like the hammer of truth ready to pound anyone who questioned her word. But he needn’t have worried because everyone simply gazed at MeMe in blank astonishment.

Java looked up at the mountain with wondering eyes for a moment, then he shouted, “Howling jackrabbits! Come on, Watson, let’s go see!”

The two cats immediately tore away across the yard, around the barn, and disappeared across the back field at the foot of the mountain.